Tight Spaces, Smart Places: Reimagining Urban School Transportation

Insight Highlights:

- Urban schools often require more careful transportation planning due to limited space

- This post covers several methods and factors Gorove Slade reviews when assisting K -12 schools in urban locations.

- This includes insights for transportation planners, school administrators, and K-12 school architects

For most school projects in the suburbs and rural areas, transportation planning is simple – build a lot of parking, add a separate school bus facility with lots of space, and then finish it with a parent pick-up/drop-off zone. However, in urban school sites, where space is at a premium, compromises have to be made, and right sizing the transportation infrastructure is essential. Otherwise, precious space that could be dedicated to fields, playgrounds, and green space ends up as asphalt used for 30 minutes twice daily.

Additionally, urban schools tend to have high percentages of students walking, and focusing on parking and parent pick-up/drop-off can conflict with walking routes, creating unsafe and inefficient uses of space. The following are three strategies Gorove Slade deploys when working in urban schools:

Minimize the Amount of Parking

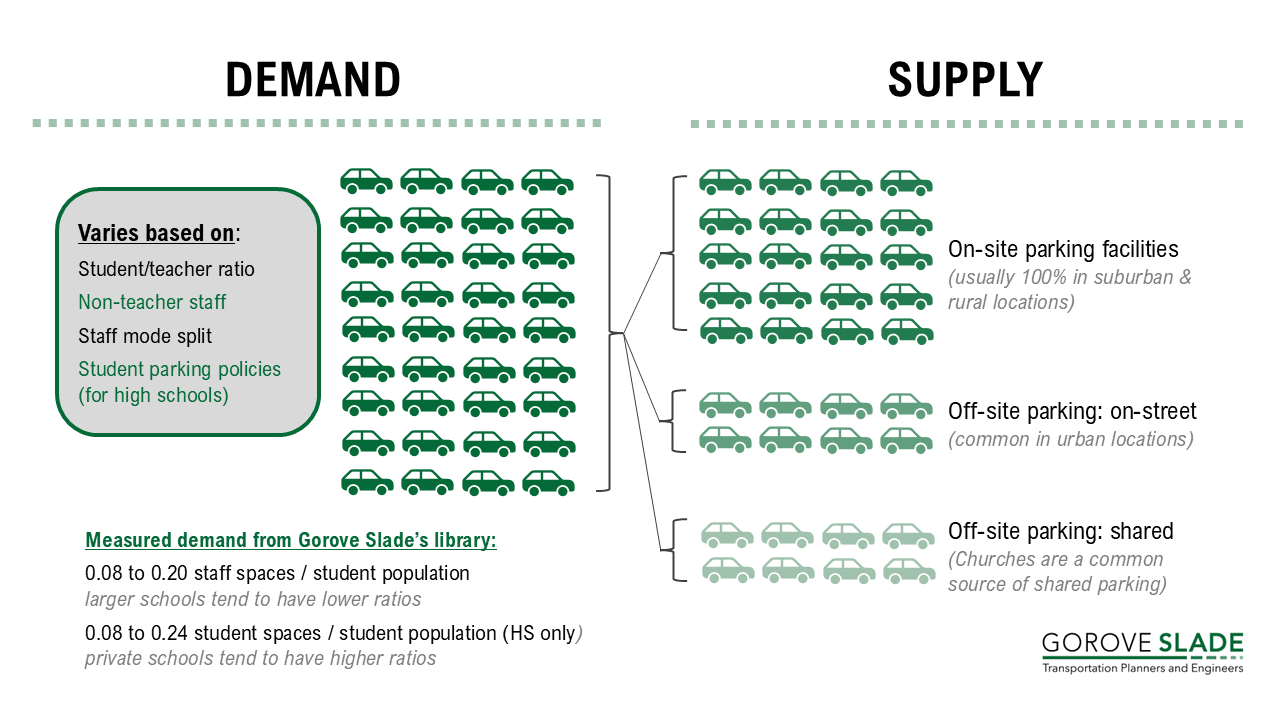

Matching the parking supply to parking demand at an urban school project can be difficult. This is because the demand varies greatly and is influenced by several factors, such as (1) the student/teacher ratio, (2) amount of non-teacher (administrative) staff, and (3) the commuting mode split of the school (i.e., how many teachers take transit, walk, bike, or don’t drive alone), and (4) for high schools, the policies allowing students to drive and park.

Over the years, Gorove Slade has collected parking demand data for a number of schools. As expected, the results vary, with larger schools tending to have fewer cars parked per student and private schools having higher parking demand. Private high schools in particular have a higher student parking demand than public high schools of similar size. We recommend thoroughly reviewing staff projections and commuting tendencies while developing a demand estimate to help plan how to accommodate demand.

With a demand estimate in hand, the next step is determining how to accommodate it, whether to build enough parking on-site or use off-site options. Often, in urban locations, there are several options off-site, including curbside on-street parking and off-site parking lots that aren’t used during the day; a common source of shared parking for schools is adjacent churches. The potential need to change the signing for on-street spaces and get written agreements with adjacent property owners to use their parking is included in evaluating off-site parking sources.

The following chart summarizes Gorove Slade’s approach to school parking supply and demand analyses:

Gorove Slade’s approach to school parking supply and demand analyses

Other factors to consider in parking supply are visitor and event parking. For visitor parking, our general approach on urban sites is to find a shared resource, for example, space in the pick-up/drop-off area that can be reserved for visitor parking between morning arrival and afternoon dismissal. Parking demand for events, such as back-to-school nights, is atypical, and it is not practical to build enough parking to accommodate atypical demand for a handful of days a year (at most). Instead, we try to accommodate event parking on shared resources on and off-site, including on-street parking and adjacent parking lots.

Minimize Room Dedicated to School Buses

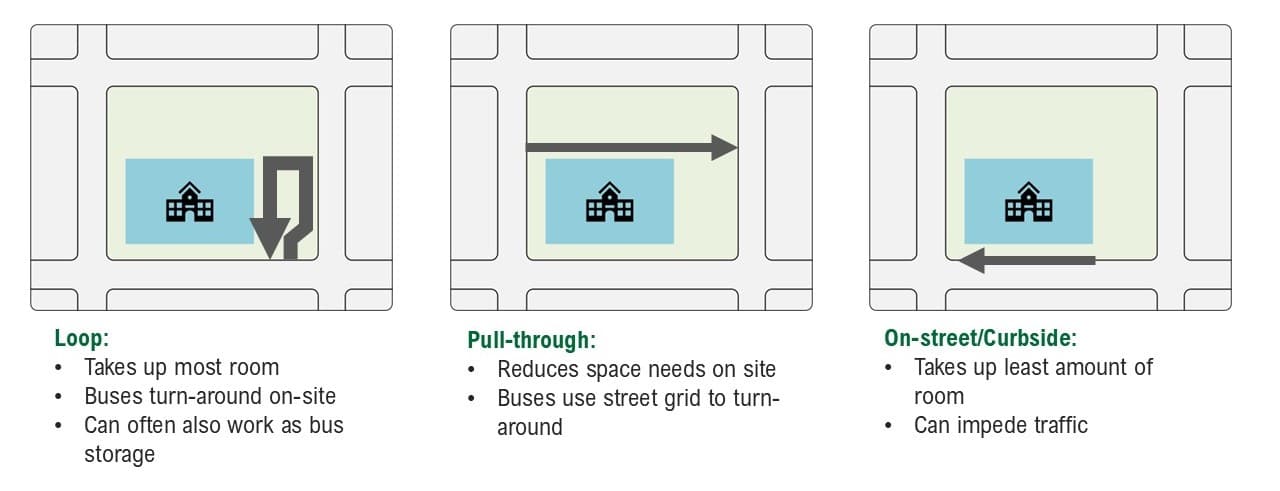

The largest factor in how much room school buses take on a school site is not where they stop, the sidewalks and boarding/alighting space students need, but how they turn around. There are three ways to handle school buses, with their main differentiation being: (1) all the bus turns happen on site, (2) part of the bus turns happen on site, and (3) none of the bus turns happen on site. These three archetypes are shown in the diagram below: loops, pull-throughs, and curbside.

The three archetypes on how to handle bus turns on a school site

The main tradeoff between these three types is control versus conflict. Control refers to how much of the facility is within the control of the school itself – the ability to control who enters the facility, how it is designed, and what happens to it outside of arrival and dismissal. For example, a ‘loop’ configuration provides the most control, such as the ability to use it for fleet storage. Meanwhile, the facilities that occupy the least space have the most conflicts. Curbside solutions can conflict with walking routes, pick-up/drop-off facilities, and non-school traffic.

The overall transportation plan for the school needs to minimize conflicts between vehicular modes and walking routes, incorporating careful consideration of what doors walking students and school bus riders are using and how those routes overlap with vehicle/bus traffic. The goal is to emphasize walking and busing to school over being dropped off and picked up via car.

Try to Get Staff and Students Out of Cars

Finally, urban schools can succeed more with programs targeted at getting staff, teachers, and students to use non-vehicular modes of travel, or at least not to drive alone. This includes infrastructure and operational measures.

When planning a school project, a review of non-vehicular infrastructure is essential, as is prioritizing modes. The student pick-up/drop-off area shouldn’t be emphasized over walking routes, biking routes, or school bus boarding/alighting. Those modes should receive priority. For new and existing school sites, a thorough review of walking and biking routes surrounding the site can reveal many opportunities to upgrade facilities, including exploring changing traffic control devices (e.g., installing all-way stop locations to aid in pedestrian crossings).

Operational measures to reduce vehicular demand, generally referred to as Transportation Demand Management (TDM), can also be applied at schools, although in a much different way than traditional land uses for commuters (e.g., residential or office). School employees often have different hours than many TDM services, sometimes must travel long distances, and are often asked to shuttle materials between locations. Because of this, we’ve seen staff carpooling as often the most successful way to reduce staff vehicular travel demand.

Traditional travel demand measures may not apply well to students, who generate most of the vehicular travel demand at schools (from pick-up/drop-off). Some jurisdictions offer free public transit to students, which can be successful, especially with older students. Otherwise, many traditional TDM strategies, such as financial incentives, don’t work either (such as parking charges). Instead, correlating alternative modes to sustainability goals and having contests to see which classrooms/homerooms can walk or bike to school the most during a month can make progress. Elementary schools can also include bike safety and education classes in their P.E. curriculum.

Carpool spaces painted by students at St. Stephen’s and St. Agnes School in Alexandria, VA

Urban school transportation planning requires a delicate balance of competing priorities – maximizing educational space while providing necessary access, ensuring safety for all travel modes, and promoting sustainable transportation choices. Gorove Slade’s experience has given us keen insights into handling these aspects and more on urban K-12 schools.

Through careful analysis of parking demands, creative solutions for bus operations, and targeted programs to encourage alternative transportation, schools, planners, and engineers can collaborate to create efficient systems that serve their campuses well. Connect with a member of our team to learn how we can help your school create a transportation plan that works for everyone – students, staff, and the surrounding community.

Urban school sites require creative solutions to balance parking, bus operations, and pedestrian safety in tight spaces. Reach out to Rob Schiesel, PE, and Daniel Solomon, AICP, to explore how we can help.